The new Aula

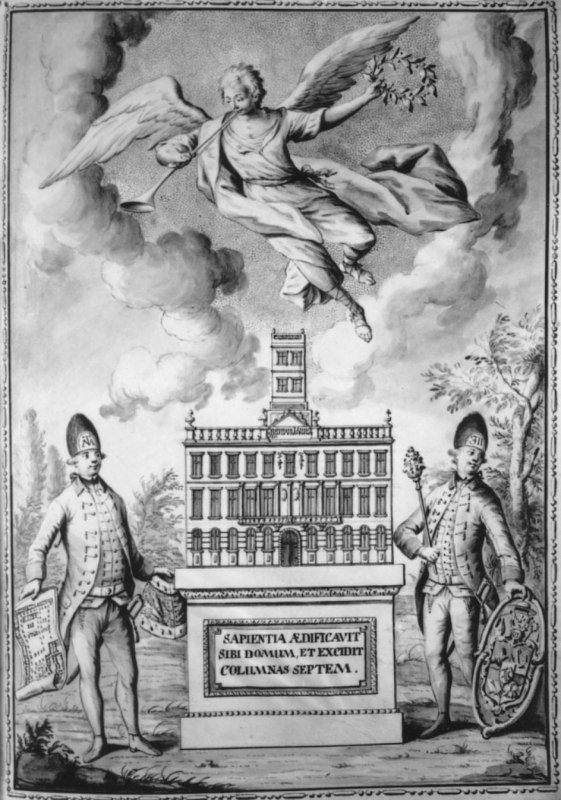

In the reigning years of the imperial couple Francis I. Stephen of Lorraine and Maria Theresia, extensive reforms were implemented in regard to the sciences and the universities. Two individuals were an integral part of these efforts: the protector of the university, Cardinal Prince-Archbishop Johann Joseph Graf von Trautson, who had advanced the study reforms of theology, philosophy and law, as well as Gerard van Swieten, president of the Medical Faculty and reformer of the study of medicine. The construction of a central university building was an expression of these reforms. In the middle of the 18th century, the various university institutions had still been dislocated and the education in theology and philosophy (since 1623) had been in the hands of the Jesuit Order. Removing these studies from the context of the Order and placing them under the care of the state was an important part of Maria Theresia’s reforms.

A building for the modernized university

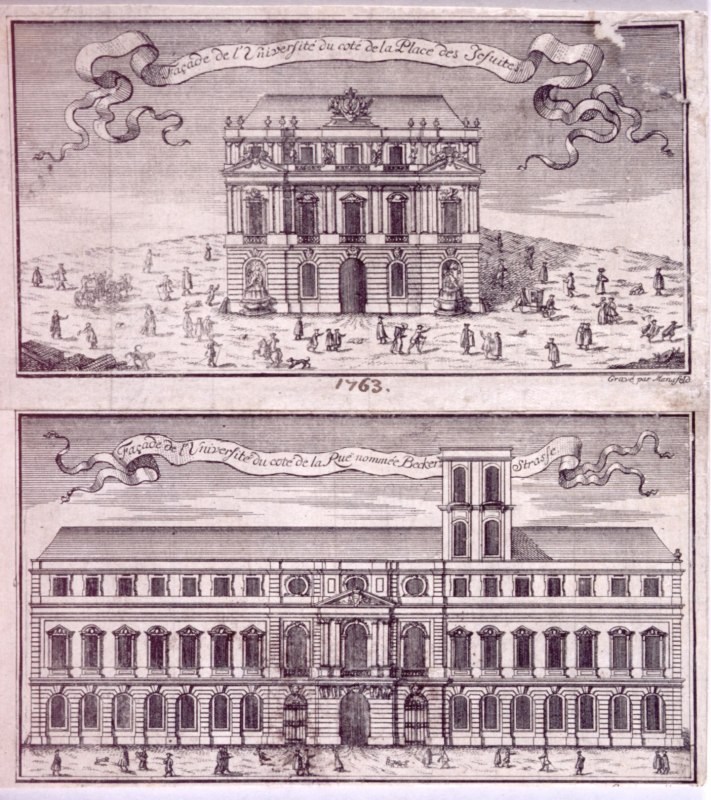

The imperial deliberations to erect a university building can be traced back to at least 1752. A building site was quickly found by buying three houses on the Western side of the “Untern Jesuiterplatzl” (“Lower Jesuit Square”). This location stayed faithful to the old university quarter that had existed since the Middle Ages, while at the same time being in direct vicinity of the Jesuit College and University and their church. The “competitive” situation made it possible to semantically change the meaning of the square characterized by the Jesuits, which was created at the same time as the college and its adjoining church had been built in the 1630s. Through a highly representative design of the main façade, the character of the square was reinterpreted and the new, modern orientation of university education was made visually evident. Lorrainese architect Jean Nicolas de Jadot masterfully achieved this goal. He had come to Vienna together with Francis I and was commissioned – among other imperial construction projects – to plan the new aula. Only a few weeks after the groundbreaking ceremony on August 10, 1753, he left Vienna, leaving the implementation of his plans to the imperial-royal deputy court architect Johann Adam Münzer with the support of Johann Enzenhofer and Daniel Christoph Dietrich.

Finished in the fall of 1755, the building was officially inaugurated by the imperial couple in April of the following year. Originally, it was only meant to house the Faculties of Law and Medicine, but at the latest in 1754 it was decided to also move the Theological and the Philosophical Faculties to the new building.

The main façade oriented towards the square is sculpturally tiered by pilasters and full columns and is arranged in a five-axis fashion. In the “piano nobile” the Corinthian style is fleshed out into a walkable pillar colonnade, similar to loge architecture: an established symbol of sovereignty. The function and benefactor of the building are recorded on the façade via sculptures and inscriptions: on the triangular gables of both side risalites, sculptures allegorically symbolize the four faculties. The imperial benefactors are represented by the monumental Habsburg-Lorraine combination crest and the inscription “FRANCISCUS I. MARIA THERESIA AUGG: / SCIENTIIS ET ARTIB: RESTITUT: POSUERUNT. MDCCLIII”.

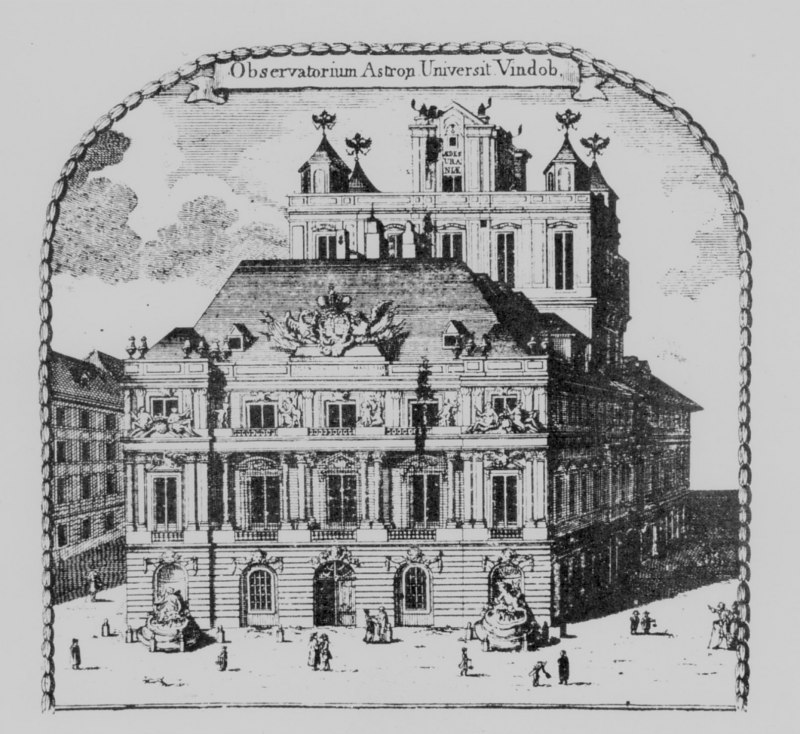

The building’s observatory represented a rare feature, which is prominently displayed in Bernardo Belotto’s famous oil painting which he created before 1760. It towered over the central part of the building, immediately behind the hipped roof on the square’s side. As later illustrations show, it was reconstructed several times. The observatory was closed down and demolished at the latest in 1879, when the new university observatory was built at the Türkenschanze.

New lecture halls and a ceremonial hall

Until today, no original plans by architect Jean Nicolas de Jadot have been found, the original layout of the lecture halls can however be reconstructed through later plans. On the ground floor, the apartment of the anatomy professor, the caretaker’s apartment and the lecture hall for “herbal science” (botany) were located on the square’s side of the building. On the other side of the ground floor were the lecture halls of the “medicine science” and the “art of dismemberment” (anatomy). The representative part of the building – an imposing columned hall with 15 Bohemian vaults on top of Doric columns – is in the center, between the two blocks of lecture halls. The first floor, the “piano nobile” is structured completely analogously, containing the ceremonial hall extending over two floors and matching the columned hall. The front, facing the square, houses the lecture halls for philosophy and theology (Johannes Hall). Behind the ceremonial hall, the lecture halls of the Faculties of Law and Economy were located (verifiable from 1796).

Only parts remain of the building’s baroque features; particularly the ceiling paintings in the ceremonial hall and the Johannes Hall are of science-historical interest. The ceremonial hall’s ceiling was painted in 1755 by Gregorio Guglielmi (figures) and Domenico Francia (illusionistic architecture) based on a concetto by the imperial court poet Pietro Metastasio. The illustrations include the four Faculties of Law, Medicine, Theology and Philosophy as well as an apotheosis of the imperial couple. Remarkably, the iconography does not exclusively follow traditional baroque allegories, but uses lasting elements of Enlightenment. In a devastating fire in 1961 the ceiling was completely destroyed and then restored by the academic painter and conservator Paul Reckendorfer.

Anti-Jesuit imagery

The Johannes Hall, the theology lecture hall, was frescoed in 1766/67 by Franz Anton Maulbertsch with “Christ’s baptism”. Unusually for iconography, the ceiling painting shows the baptism as the manifestation of the trinity and is thus directed against Jesuit anti-trinitarianism – it can be interpreted as an expression of the fight against the Jesuit teachings. This fresco is considered one of the most important early works of the most distinguished Austrian painter in the late baroque.

Between 1759 and 1786 the new aula also housed the Academy of Fine Arts on its second floor. After the revolution of 1848 was defeated, the military occupied the building and was used as “aula barracks” until the “defensive barracks” (Roßauer barracks, Franz Joseph barracks) that controlled the city were finished. In 1857 the building was not given back to the university, but to the Academy of Sciences, whose seat it is until today.

-

Fassadenansicht der Neuen Aula (1763)

-

Anatomisches Theater im theresianischen Aulagebäude (1786)

Die Neue Aula verfügte auch über ein anatomisches Theater, welches sich nicht erhalten hat. (Rektorsblatt in der Wiener Universitätsmatrikel, Kod. M...

-

Rektorsblatt zur Neuen Aula mit Sternwarte

-

Die Neue Aula mit Sternwarte (Observatorium)

Last edited: 03/04/24